![]() Nickerie.Net,

woensdag 15 oktober 2008

Nickerie.Net,

woensdag 15 oktober 2008

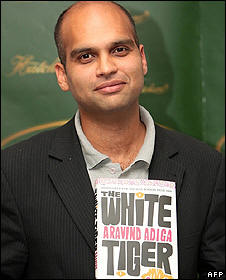

LONDEN (ANP) - De Indiase schrijver Aravind Adiga heeft de Booker Prize 2008 gekregen voor zijn debuutroman De Witte Tijger. Dat maakte de jury van de prestigieuze literatuurprijs dinsdag bekend. Volgens juryvoorzitter Michael Portillo ,,schokt en vermaakt het boek in gelijke mate''.

De

33-jarige Adiga kreeg de prijs en een cheque van 50.000 Britse pond (64.000

euro) overhandigd tijdens een ceremonie in Guildhall, Londen. Het is pas de

derde keer in vier decennia dat een debuterend schrijver de prijs krijgt.

De

33-jarige Adiga kreeg de prijs en een cheque van 50.000 Britse pond (64.000

euro) overhandigd tijdens een ceremonie in Guildhall, Londen. Het is pas de

derde keer in vier decennia dat een debuterend schrijver de prijs krijgt.

Het bekroonde boek, volgens de jury ,,origineel, fascinerend, boos en zwartgallig humoristisch'', gaat over de ontwikkeling van een man die het vanuit een klein Indiaas dorp schopt tot succesvol ondernemer.

De in Madras geboren en in Mumbai (voorheen Bombay) woonachtige Adiga schaart zich in een fameuze rij Indiase auteurs die de Booker Prize wonnen. VS Naipaul (1971), Salman Rushdie (1991), Arindhati Roy (1997) en Kiran Desai (2006) gingen hem voor.

Adiga studeerde aan de universiteiten van Columbia (VS) en Oxford (Groot-Brittannië) en werkte als correspondent voor het Amerikaanse tijdschrift Time in India. Zijn verhalen verschenen ook in kranten als de Financial Times, de Independent en Sunday Times.

NRC handelsblad, 15-10-2008

Aravind Adiga wint Booker Prize

Dat maakte de jury van de prestigieuze literatuurprijs dinsdag bekend. Volgens juryvoorzitter Michael Portillo ,,schokt en vermaakt het boek in gelijke mate''.

Rob van Essen schreef dinsdag over The White Tiger het volgende:

'The

White Tiger van Aravind Adiga bestaat uit brieven die Balram Halwai, een

succesvol zakenman, midden in de nacht aan de premier van China schrijft.

'The

White Tiger van Aravind Adiga bestaat uit brieven die Balram Halwai, een

succesvol zakenman, midden in de nacht aan de premier van China schrijft.

Balram heeft gehoord dat de premier naar India komt om zich te verdiepen in het succes van Indiase ondernemers, en dat is een onderwerp waar hij als ervaringsdeskundige alles van weet.

Waarna hij de premier vol enthousiasme zijn levensverhaal begint te vertellen, wat en passant een onthutsend beeld van het tegenwoordige India oplevert (achterlijk en corrupt).

The White Tiger is een strak maar uitbundig boek waar het vertelplezier vanaf spat, dat je in één ruk uitleest – waarna je je afvraagt waarom je je in godsnaam door de verteller hebt laten inpakken. Niemand moet vreemd opkijken als vanavond Aravind Adiga de Booker Prize wint.'

Recentie: Nu.nl

Aravind Adiga – De Witte TijgerBalram Halwai is de witte tijger: het slimste jongetje uit het straatarme dorp waar zijn enige toekomst er een is van schrapen, honger lijden, vernedering, armoe en ongelijkheid. Zijn familie kan zich niet veroorloven om de jongen op school te houden, en verkoopt hem als bediende om hun schuld van de bruidsschat in te lossen. Balram ruikt zijn kans als hij erin slaagt om een baantje als privéchauffeur te bemachtigen.

Kookpunt

Zijn geluk krijgt Olympische proporties als zijn werkgever naar Delhi verhuist,

en Balram meeneemt. In de grote stad ontdekt Balram de rijkdom en weelde die

exclusief is voorbehouden aan de allerrijksten. Terwijl hij zit te broeden op

een plan om zich aan zijn martelende kaste te ontworstelen, krijgt hij de ene

vernedering na de andere onrechtvaardigheid te slikken tot het een kookpunt

bereikt.

J'accuse

Witte Tijger is een J'accuse, een bittere aanklacht tegen een land dat in deze roman niet bepaald wordt bezongen om de keuken, de geuren, de kruiden, de kleuren, en lachende kinderen met glanzend zwarte ogen. Adiga omschrijft India als een ren vol hanen die op elkaar zitten gepropt, vechtend om een ademtocht en die moordend woest tekeer gaan om die ene rijstkorrel. Waar hij vandaan komt noemt Balram het Donker, waar hij heen wil het Licht.

Valse honden

Het verschil tussen arm en rijk is zo schrijnend, dat er in de vertrapte onderlaag valse honden worden gekweekt. Het is een kwestie van vreten of gevroten worden; als je wilt overleven, is er geen andere keuze dan smeergeld, verraad, geweld, wreedheid of de ander verlinken. Adiga maakt die grimmigheid, die voor tientallen miljoenen Indiërs dagelijkse realiteit is, zeer voelbaar. Zijn verhaal is schokkend realistisch en de enige schoonheid die is te ontdekken, is zijn zuivere proza en sardonische stijl. Want wat kan deze man schrijven.

Briefvorm

Adiga vertelt de levensgeschiedenis van Balram vanuit de ik-persoon, en het verhaal is opgebouwd als een lange brief aan de premier van China die op het punt staat zijn land te bezoeken. Balram is inmiddels entrepreneur, en hij wil dat de premier de waarheid over zijn land verneemt voordat hij zich stroop om de mond laat smeren tijdens het officieel bezoek.

Moord

Balram heeft gemoord, daar windt hij geen doekjes om. Hij heeft gemoord om te bereiken wat hij nu heeft, en al na het eerste hoofdstuk waarin hij zijn leven via flashbacks uit de doeken doet, is hem die misdaad niet eens aan te rekenen. Als Balram in een ander land en in een ander systeem was geboren, had hij het heel anders aangepakt. Want dit personage wekt sympathie op zonder in de slachtofferrol te vervallen – al zit hij vanwege zijn afkomst in een slachtofferhoek die voor hem lijkt te zijn uitgestippeld.

Ontsnapte haan

Maar een inspecteur op school is de eerste die hem vertelt dat hij 'anders' is. Balram is als een witte tijger, zegt hij, dat magische jungledier dat maar één keer in een generatie opduikt. De jungle waar Balram mee te maken krijgt, is de Indiase maatschappij – en daarin zijn de geurende jasmijnvelden of gele saffraanheuvels ver te zoeken. Dat er één haan uit die ren is ontsnapt, doet je aan het eind van dit boek een zucht slaken van verlichting. Dat die haan een witte tijger betreft die uiterst zeldzaam is, niet. Maar wat een boek.

Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij.

Oorspronkelijke titel: The White Tiger.

Prijs: € 18,90

288 pagina's

ISBN 978 90 234 2895 4

Interview

Who

are some of your literary influences? Do you identify yourself particularly as

an Indian writer?

Who

are some of your literary influences? Do you identify yourself particularly as

an Indian writer?

It might make more sense to speak of influences on this book, rather than on me.

The influences on The White Tiger are three black American writers of the

post-World War II era (in order), Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin, and Richard

Wright. The odd thing is that I haven't read any of them for years and years --

I read Ellison's Invisible Man in 1995 or 1996, and have never returned

to it -- but now that the book is done, I can see how deeply it's indebted to

them. As a writer, I don't feel tied to any one identity; I'm happy to draw

influences from wherever they come.

Could you describe your process as a writer? Was the transition from

journalism to fiction difficult?

A first draft of The White Tiger was written in 2005, and then put aside.

I had given up on the book. Then, for reasons I don't fully understand myself,

in December 2006, when I'd just returned to India after a long time abroad, I

opened the draft and began rewriting it entirely. I wrote all day long for the

next month, and by early January 2007, I could see that I had a novel on my

hands.

From where did the inspiration for Balram Halwai come? How did you capture

his voice?

Balram Halwai is a composite of various men I've met when traveling through

India. I spend a lot of my time loitering about train stations, or bus stands,

or servants' quarters and slums, and I listen and talk to the people around me.

There's a kind of continuous murmur or growl beneath middle-class life in India,

and this noise never gets recorded. Balram is what you'd hear if one day the

drains and faucets in your house started talking.

This novel is rich in detail -- from the (often corrupt) workings of the

police force to the political system, from the servant classes of Delhi to the

businessmen of Bangalore. What kind of research went into this novel?

The book is a novel: it's fiction. Nothing in its chapters actually

happened and no one you meet here is real. But it's built on a substratum of

Indian reality. Here's one example: Balram's father, in the novel, dies of

tuberculosis. Now, this is a make-believe death of a make-believe figure, but

underlying it is a piece of appalling reality -- the fact that nearly a thousand

Indians, most of them poor, die every day from tuberculosis. So if a

character like Balram's father did exist, and if he did work as a rickshaw

puller, the chances of his succumbing to tuberculosis would be pretty high. I've

tried hard to make sure that anything in the novel has a correlation in Indian

reality. The government hospitals, the liquor shops, and the brothels that turn

up in the novel are all based on real places in India that I've seen in my

travels.

In the novel, you write about the binary nature of Indian culture: the Light

and the Darkness and how the caste system has been reduced to "Men with Big

Bellies and Men with Small Bellies." Would you say more about why you think the

country has come to be divided into these categories?

It's important that you see these classifications as Balram's rather than as

mine. I don't intend for the reader to identify all the time with Balram: some

may not wish to identify with him very much at all. The past fifty years have

seen tumultuous changes in India's society, and these changes -- many of which

are for the better -- have overturned the traditional hierarchies, and the old

securities of life. A lot of poorer Indians are left confused and perplexed by

the new India that is being formed around them.

Although Ashok has his redeeming characteristics, for the most part your

portrayal of him, his family, and other members of the upper class is harsh. Is

the corruption as rife as it seems, and will the nature of the upper class

change or be preserved by the economic changes in India?

Just ask any Indian, rich or poor, about corruption here. It's bad. It shows no

sign of going away, either. As to what lies in India's future -- that's one of

the hardest questions in the world to answer.

Your novel depicts an India that we don't often see. Was it important to you

to present an alternative point of view? Why does a Western audience need this

alternative portrayal?

The main reason anyone would want to read this book, or so I hope, is because it

entertains them and keeps them hooked to the end. I don't read anything because

I "have" to: I read what I enjoy reading, and I hope my readers will find this

book fun, too.

I simply wrote about the India that I know, and the one I live in. It's not "alternative

India" for me! It's pretty mainstream, trust me.

How did your background as a business journalist inform the novel, which has

as its protagonist an entrepreneurial, self-made man? With all the changes India

is undergoing, is it fostering change within its population, or are the

challenges and costs of success as great as they were for Balram?

Actually, my background as a business journalist made me realize that most of

what's written about in business magazines is bullshit, and I don't take

business or corporate literature seriously at all. India is being flooded with "how

to be an Internet businessman" kind of books, and they're all dreadfully earnest

and promise to turn you into Iacocca in a week. This is the kind of book that my

narrator mentions, mockingly -- he knows that life is a bit harder than these

books promise. There are lots of self-made millionaires in India now, certainly,

and lots of successful entrepreneurs. But remember that over a billion people

live here, and for the majority of them, who are denied decent health care,

education, or employment, getting to the top would take doing something like

what Balram has done.

One thing at the heart of this novel, and in the heart of Balram as well, is

the tension between loyalty to oneself and to one's family. Does this tension

mirror a conflict specific to India, or do you think it's universal?

The conflict may be more intense in India, because the family structure is

stronger here than in, say, America, and loyalty to family is virtually a test

of moral character. (So, "You were rude to your mother this morning" would be,

morally, the equivalent of "You embezzled funds from the bank this morning.")

The conflict is there, to some extent, everywhere.

What is next for you? Are you working on another novel?

Yes!

Unless otherwise stated, this interview is reproduced with permission of the

author or the author's publisher. It is prohibited to reproduce this interview

in any form without written permission from the copyright holder.

(Copyright: Book Browse)

|

Bron/Copyright: |

|

|

Nickerie.Net / BBC / Book Browse |

14-10-2008 |

|

|

E-mail: info@nickerie.net

Copyright © 2008. All rights reserved.

Designed by Galactica's Graphics